A high-resolution model of how soil erosion impacts the carbon cycle of a small South Carolina watershed may help explain an apparent imbalance in the world’s carbon budget. Explaining that apparent imbalance is necessary for understanding and predicting the course of global climate change.

A high-resolution model of how soil erosion impacts the carbon cycle of a small South Carolina watershed may help explain an apparent imbalance in the world’s carbon budget. Explaining that apparent imbalance is necessary for understanding and predicting the course of global climate change.

Researchers from four U.S. universities have created a high-resolution model that shows how localized soil erosion transfers and buries soil organic carbon in streams and other deposition sites.

“Recent attempts to estimate global carbon budgets have identified a missing sink of significant size,” said Yannis Dialynas, a hydrology Ph.D. student in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “We believe this can be partly explained by the erosion of soil and the burial of organic matter in streams and rivers.”

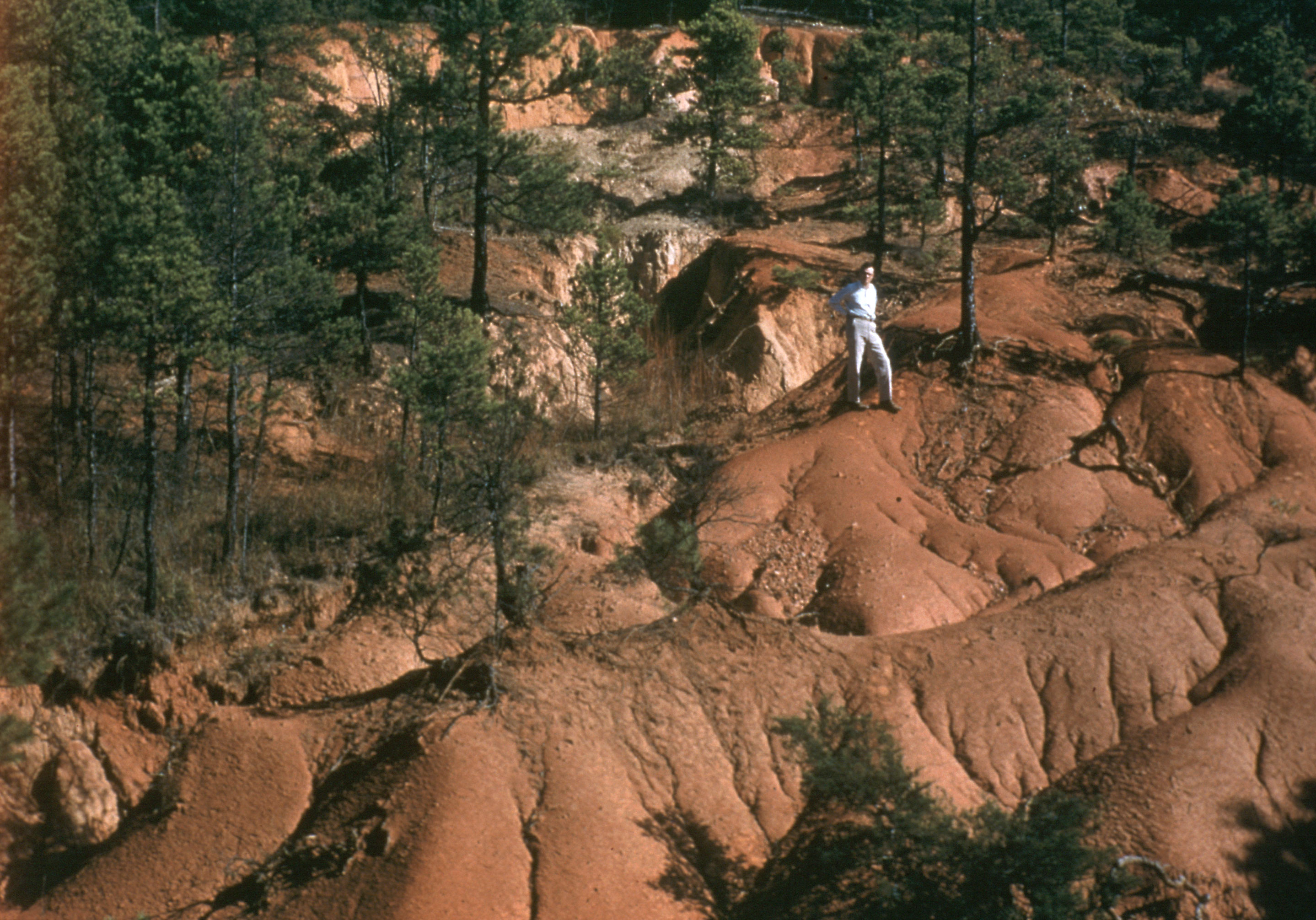

In a project sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF), researchers from Georgia Tech, Duke University, the University of Georgia and the University of Kansas studied soil eroding from the Holcombe’s Branch watershed, a 4.3-square-kilometer area that is part of the NSF’s Calhoun Critical Zone Observatory in South Carolina. The watershed has suffered dramatic land degradation caused by intense agricultural practices over the past century.

Based on a detailed study of hydrologic, geomorphic and biogeochemical processes in the watershed, the researchers developed a high-resolution computer model of the mechanisms responsible for carbon transport. The Triangulated Irregular Network-based Real-time Integrated Basin-Simulator-Erosion and Carbon Oxidation (tRIBS-ECO) model, allowed the researchers to quantify key features governing the soil-atmosphere carbon exchange, including the fate of eroded carbon at the watershed scale and the replacement rate of eroded carbon by atmospheric carbon sequestration.

“This is the first model that couples physics-based formations of hydrologic, geomorphic and biogeochemical processes into a spatially-explicit model,” said Dialynas, who is a member of the research team of Rafael L. Bras, Georgia Tech Provost and professor in the schools of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “The model systematically accounts for dynamic feedbacks among linked processes. We have validated the performance of the model based on observations and measurements of organic material from diverse soil profiles.”

The research was reported May 11 in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, which is published by the American Geophysical Union.

Atmospheric carbon dioxide is transferred to plants and then to soils in the form of soil organic carbon. Part of organic matter at eroding soils is decomposed by microbial processes, leading to carbon release into the atmosphere. Erosion-induced carbon fluxes depend on human impacts, including the use of fertilizers during agricultural operations. Soil erosion can transfer and bury upland soil organic carbon in depositional sites, where it can be protected from decomposition.

“Soils can act as a net carbon source or a carbon sink, and we have shown that land management practices have a significant influence on the landscape’s capacity to serve as a net carbon sink or a source. This may change over time depending on agricultural practices and forest cover,” Dialynas said.

The model accounts for topographic gradients in the complex morphology of a watershed, and considers how specific episodes – such as heavy rains – drive the erosion process. Earlier models were not able to systematically account for these factors, and most of them considered erosion a continuous process.

Among the conclusions from this research:

- Land management practices exert strong control on the landscape’s capacity to serve as a net carbon sink or carbon source in response to geomorphic and other perturbations.

- Erosion-induced carbon fluxes exhibit significant topographic variation at relatively small – tens of meters – spatial scales, which cannot be ignored in carbon budgets.

- Accounting for small-scale heterogeneity in topography and episodic erosion rates can influence model projections of carbon exchange with the atmosphere.

While the model was developed to explain carbon dynamics on gullied South Carolina farmland, the researchers suggest that it can also be used to assess the impact of soil management and soil erosion at other locations. Among future steps, the researchers plan to apply tRIBS-ECO to sites where erosion has been accelerated by human activity, and in areas where intense hydro-meteorological phenomena and geomorphic gradients have the potential to induce significant sediment transport and carbon cycling.

“Soils have the potential to act as significant sinks of carbon dioxide,” Dialynas said. “By accounting for the effects of erosion on the net soil-atmospheric carbon exchange, we may be able to better understand future challenges posed by climate change. What we are seeing in South Carolina could be extrapolated to other areas with disturbed soils and human impacts.”

In addition to those already mentioned, the research team included Satish Bastola, Sharon A. Billings, Daniel Markewitz and Daniel deB. Richter.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant EAR1331846. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

CITATION: Yannis G. Dialynas, et al., “Topographic variability and the influence of soil erosion on the carbon cycle,” (Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2016). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/2015GB005302

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contacts: John Toon (jtoon@gatech.edu) (404-894-6986) or Ben Brumfield (ben.brumfield@comm.gatech.edu) (404-385-1933).

Writer: John Toon