Researchers linked the 2014-2015 marine heatwave – often referred to as the “warm blob” – to weather patterns that started in late 2013.

The Northeast Pacific’s largest marine heatwave on record was at least in part caused by El Niño climate patterns. And unusually warm water events in that ocean could potentially become more frequent with rising levels of greenhouse gases.

That’s the findings of a new study by researchers from Georgia Institute of Technology and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. They linked the 2014-2015 marine heatwave – often referred to as the “warm blob” – to weather patterns that started in late 2013. The heatwave caused marine animals to stray far outside of their normal habitats, disrupting ecosystems and leading to massive die-offs of seabirds, whales and sea lions.

The study, which was published July 11 in journal Nature Climate Change, was sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

“We had two and a half years of consistent warming, which translated to a record harmful algal bloom in 2015 and prolonged stress on the ecosystem,” said Emanuele Di Lorenzo, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “What we do in the study is ask whether this type of activity is going to become more frequent with greenhouse gases rising.”

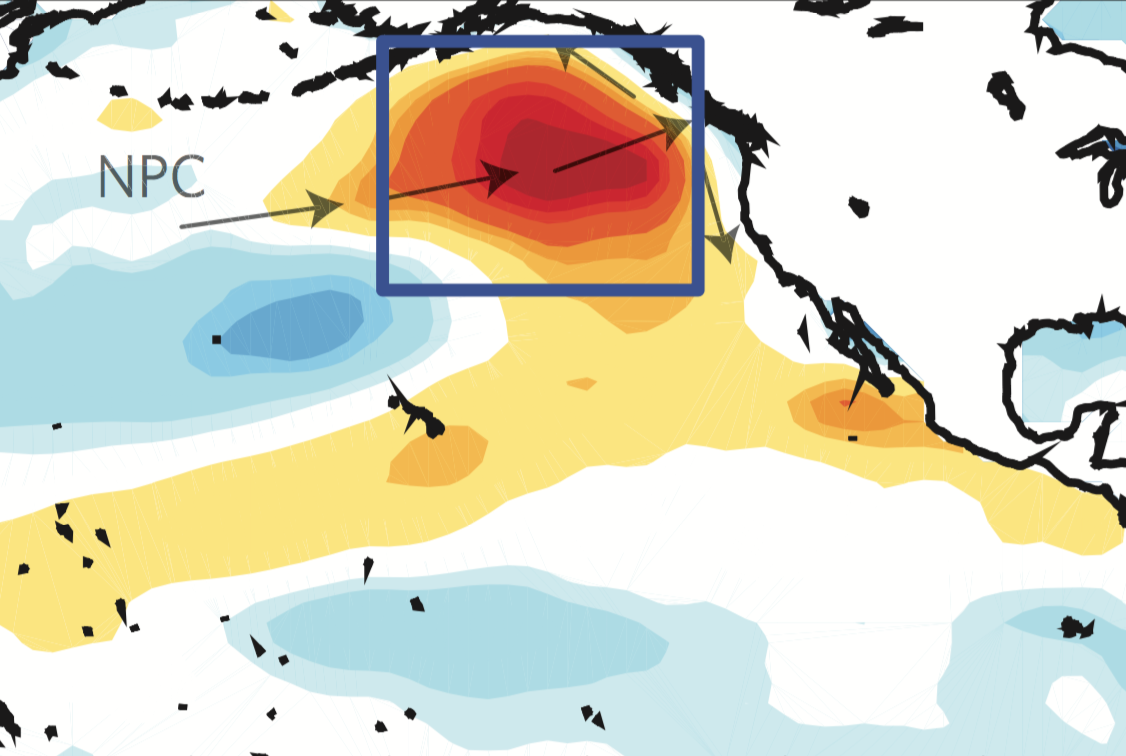

The researchers traced the origin of the marine heat wave to a few months during late 2013 and early 2014, when a ridge of high pressure led to much weaker winds that normally bring cold Artic air over the North Pacific. That allowed ocean temperatures to rise a few degrees above average.

Then, in mid-2014 the tropical weather pattern El Niño intensified the warming throughout the Pacific. The warm temperatures lingered through the end of the year, and by 2015 the region of warm water had expanded to the West Coast, where algal blooms closed fisheries for clams and Dungeness crab.

“The bottom line is that El Niño had a hand in this even though we’re talking about very long-distance influences,” said Nate Mantua, a research scientist at NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center and a coauthor of the study.

The researchers used climate model simulations to show the connection between increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and the impact on the ocean water temperatures. The study found that these extreme weather events could become more frequent and pronounced as the climate warms.

“This multi-year event caused extensive impacts on marine life,” Di Lorenzo said. “For example, some salmon populations have life cycles of three years, so the marine heatwave has brought a poor feeding, growth and survival environment in the ocean for multiple generations. Events like this contribute to reducing species diversity.”

And the effects of the “warm blob” could linger.

“Some of these effects are still ongoing and not fully understood because of the prolonged character of the ocean heatwave,” Di Lorenzo said. “Whether these multi-year climate extremes will become more frequent under greenhouse forcing is a key question for scientists, resource managers and society.”

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. OCE 1356924 and OCE 1419292. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

CITATION: Emanuele Di Lorenzo and Nathan Mantua, “Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15

North Pacific marine heatwave,” (Nature Climate Change, July 2016).